This is the eighth part of The Ancients, a series of posts which, by this time, I’m pretty sure all you natural history buffs (Pretty sure you qualify for that by now) know, so I’ll get straight to the point. Check out parts 1-7 before this one!

Quick info:

Name: Carboniferous

Period: 358.9-298.9 m.y.a

Average Temperature: 14 Celsius

Atmospheric oxygen : 32.5%

Remember how there was a mass extinction during the Devonian? Well, guess what, there was another one during this eon. WOOP-DE-DOO! Of course, there had to be another one. Luckily, this one wasn’t that bad; but more on that later. During the Carboniferous, most of the coal deposits we use today were formed (That’s why it’s called the Carboniferous). The two continents that had slowly formed during the Devonian and Silurian, Gondwana and Euramerica (because it’s made up of land that will eventually form Europe and North America), were starting to join, forming the Appalachian and Variscan mountain ranges. Since all the land was near the South end of the Earth, an ice cap formed at the South pole, and, FINALLY, after SO MUCH EVOLUTION, four-legged vertebrates evolved in the coal swamps of the Equator.

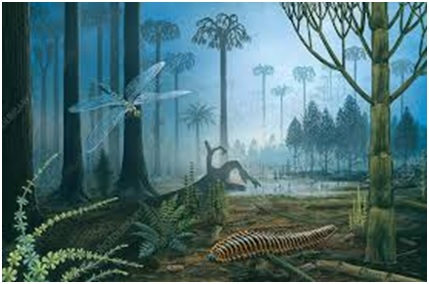

But first, the Carboniferous Collapse. Opportunistic ferns started to gain height, and rainforests started to shrink, each ‘island’ of rainforest developing their own animal species, when before, the same species existed throughout the rainforest. The rainforest patches were surrounded by an unsuitable habitat, which led to animals evolving in different ways inside each patch. Before the Collapse though, trees were everywhere, and oxygen levels rose, and something HUGE happened. But first, you have to understand a bit of Entomology ( study of insects).

Insects don’t have lungs. That much is obvious. Now, while we humans have one trachea, insects have a whole system of tracheal tubes. Each tube has an opening on the insect’s body, and oxygen is brought in through the tubes, through a whole web-like system to reach all tissues, and carbon dioxide is brought out. As the insect get’s bigger, the tubes elongate to reach longer limbs, and increase in either diameter or number to accommodate the additional oxygen needs. However, the openings can only get so big, and that limits growth. When there is a surplus of oxygen, an insect can grow much bigger.

Remember, in the Silurian, a giant millipede called Pneumodemus ? Yeah, imagine tons of other insects the same size. Almost as big as a human. They also grew because of the lack of terrestrial predators (That’s why, in later periods with similar oxygen levels, there were no giant insects). But, after the Collapse, oxygen levels receded, and insects became smaller. Due to the decrease in rainforests, the humidity also decreased, and so a hot, dry climate evolved, killing off many species of amphibian, but promoting the evolution of reptiles. This event also promoted the creation of coal. How? Wait and see.

Coal only forms when an organism does not decompose, and release all the carbon into the atmosphere, but instead, the carbon is pressurized underground. The Carboniferous was full of coal due to the abundance of swamps, which naturally inhibit decomposition. Animals, plants and decomposing bacteria had also not evolved the specialized enzymes and chemicals to break down the substances present in the dead organisms. However, towards the end of the Carboniferous, fungi arose which could break down said substances, and this made coal formation in the later periods much rarer.

Now, there were many species of tree in each patch of rainforest, but the three most prosperous, abundant, and ones which made the biggest rainforests were, Lepidodendron, Sigillaria, and Calamites. Lepidodendron was a tree which could grow over 30m in height, and probably only reproduced at the end of its lifespan. Sigillaria was closely related to Lepidodendron, and had a very short lifespan of around 13 years. Lastly, Calamites were actually tree-ferns, specifically horsetails. Now, for some crazy fish. Akmonistion was related closely to sharks, and had a crest which looked a lot like an anvil instead of the iconic dorsal fin. This crest had barbs on it, and so did its forehead. Helicoprion was another shark-like fish which lived very long. Its lower teeth were arranged in a spiral pattern which could hang outside of its mouth. The species of reptiles, among others, were Hylonomus, a small, 20-centimetre long reptile which fed mostly on insects (before and after they became supersized) and Archaeothyris, which looked like a lizard, and could grow up to 50cm long. It was actually the ancestor of synapsids, (soon-to-be modern-day mammals; don’t worry, I’ll explain in the next blog!). The giant insects are next. Pulmonoscorpius was a species of giant scorpion, almost 70 centimetres long. It ate small arthropods and could kill some tetrapods as well. Arthropleura was one of the biggest insects, at 2.3 metres in length and 50 centimetres wide. It had very few predators, and has actually herbivorous. It’s like the insect version of an elephant! Lastly, Meganeura was a genus of dragonflies, which could have a wingspan of 65 centimetres.

There’s more to come. And it will get more confusing as we go on. Patience bears fruit, sweet or not, we will get to that some other time.

Shaurya Prasad (Grade 7)